Early parliamentary elections in Japan concluded with a convincing victory for the Liberal Democratic Party led by Sanae Takaichi — already dubbed the "Iron Chancellor." The ruling party has not received such support since World War II. Yuriy Romanenko speaks with diplomat and Asian affairs expert Serhiy Korsunsky, former Ukrainian Ambassador to Japan and Turkey, about what this result means for regional security, why Japan is creating its own intelligence service and launching a massive rearmament program, how middle powers are responding to the challenges of the new era, and why George Friedman's theses about their weakness are mistaken.

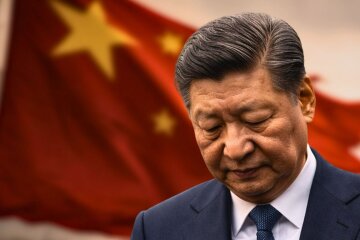

The conversation covers analysis of the Munich Conference and U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio's speech, the crisis in China's economy and internal problems of Xi Jinping's regime, the unexpected successes of the Trump administration in the Caucasus, the concept of the "first island chain" in the Pacific, and the prospects for Ukrainian-Japanese relations. Also included — reflections on why Vladimir Putin's actions awakened Germany and Japan, united NATO, and created conditions for strengthening precisely those countries that were supposed to become weaker.

Yuriy Romanenko: Friends, hello everyone! Surfer slackers, beloved deviants. We're starting our broadcast today. And we're starting early today, because our guest is Serhiy Korsunsky. You know him well — former Ukrainian Ambassador to Japan. He lives in Japan now, works there, teaches. And we do these broadcasts about once a month. I try not to do them too often, though honestly I'd gladly do one every week, it's that interesting. On the other hand, I understand that every intellectually developed person and speaker shouldn't burn out in intellectual battles, so I try to use his intellectual resources carefully. And so with great pleasure we're resuming our communication today. Serhiy, good evening to you!

Serhiy Korsunsky: Good evening, good day!

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, well, there have been several important events, as they say, over the past few weeks. At the beginning of February, Japan held early elections, and the Liberal Democratic Party led by Sanae Takaichi won by a landslide. This woman — the Iron Chancellor — will probably go down in Japan's history, I suspect, I have that suspicion. And clearly what is happening in Japan now, and the course she is now setting — we'll talk about that a bit later — is directly connected to the collapse of the world order happening before our eyes. And we saw elements of this collapse, the fixing of this collapse, at the Munich Conference, where many notable figures appeared — Hillary Clinton was there, Marco Rubio arrived, the U.S. Secretary of State, Macron shone alongside Scholz with their statements, and Zelensky naturally made his mark. But essentially I get the feeling that for now everyone remains at their own position.

Marco Rubio — I read what you wrote, and I'll probably agree with your assessment, though I wrote about it and framed the topic — Lord, what did we call it — this turn of Marco Rubio in Munich. But I get the feeling it was just a good cop/bad cop game. Last Munich, Vance came and scared everyone. This time Rubio came, patted everyone on the head, and already the European press, happily wagging their tails, says: "No, it's not all that scary, comrade commissar, not all that scary..." That's my impression. What do you say?

Serhiy Korsunsky: There was indeed a strange feeling when, first of all, they gave him a standing ovation, and second, the Europeans breathed a sigh of relief as if a mountain had fallen from their shoulders. I think they rejoiced a bit prematurely. Rubio did say many of the right things in a significantly softer form than Vance. But the speech isn't really the point. You have to read the documents. The approved documents exist, and even for the Trump administration, America has a tradition of following the defined course. And in that defined course it's clearly written: now everyone is on their own. Guys, in Europe, these are your problems. Deal with Europe — our domain is the Western Hemisphere, that's ours.

Of course, Rubio still perceives the situation more soberly than other figures currently involved in American foreign policy. He does understand what's happening, understands the importance of ties, but even he cannot deviate from the policy Trump preaches. He preaches the localization of security. And forward. Here in Asia, this is all perceived very painfully, because the situation here is no better than in Europe. In Europe there's just Russia, but here there's also China and North Korea. You can imagine the tension.

Yuriy Romanenko: So in essence, nothing fundamentally changes — that's my brief summary of your short speech. Nothing fundamentally changes. Everyone is on their own, Europe needs to get moving.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Well, they're trying to get moving there, of course. But, as always, very slowly.

Yuriy Romanenko: Ukraine too — in my understanding, based on the statements that were made, there was nothing principally new either. So we're preparing, moving forward?

Serhiy Korsunsky: Europe is moving at the pace at which it moves. Extraordinarily amusing for... All of Asia is laughing here. There was this statement by Wang Yi, who said Japan dreams of attacking Taiwan to make it a colony again. I haven't seen 120 million people laugh like that in a long time!

Yuriy Romanenko: And what are these 120 million people going to do in the context of the early parliamentary elections and the stunning victory?

Serhiy Korsunsky: Yes, they voted, all is well. Takaichi received support unseen since World War II. Never before has the ruling party received a majority of this kind. And the coalition — 352 seats altogether, that's something incredible. And Takaichi — well done, she played her cards at the right moment. There was a very serious risk, because calling elections three months after forming a government, when the government hasn't really accomplished much yet... But the result exceeded all expectations.

And to our joy — our Ukrainian joy, I mean — several odious figures who were there, who were against Ukraine and who seriously obstructed us, did not make it into parliament. I quarreled with them quite seriously in my time. They were not elected. And conversely — several new faces entered parliament within the LDP who very strongly support Ukraine and know Ukraine well. I am very glad about this, because we will definitely need to build relations now, since what has happened will most likely be for the long term. It's hard to imagine elections in the near future. So a minimum of three years for this government, as it was under Kishida. It will be formed literally within a few days, but no changes are expected compared to the previous government. And onward.

There is a huge agenda that includes revising all strategic security documents. Japan is creating a national intelligence structure. Next year, the creation of what we call a foreign intelligence service is expected. None of this existed before. There will be a serious rearmament program. And simultaneously with all of this, there will be economic stimulus in those sectors where China tried to obstruct Japan.

For example, just today I read that a second voyage ship has gone out to sea, going to the ocean and raising from a depth of six kilometers — these are not stones, they're like deposits, you know, a kind of suspension. And they discovered an absolutely unimaginable quantity of rare earth metals there, which China is not selling to Japan or barely selling, using them to blackmail everyone. So the Japanese, instead of trying to negotiate with them as some others have tried to do, simply said: "Well then, we'll just raise them from the seabed." And it's much easier and cheaper to refine the deposits, because it's not ore, it's essentially a liquid medium. Problem solved.

Likewise in Hokkaido — in addition to one chip factory already built — another factory for manufacturing state-of-the-art chips will be built in Hokkaido together with a well-known Taiwanese company. And that's it. You tried to push Japan around — Japan will give you an answer. It won't debate the idiotic thesis that it plans to capture Taiwan. That's nonsense. It's simply impossible under any circumstances. But returning economic momentum — they'll do that. And they'll learn to manufacture weapons and sell them. So that's another brilliant result.

By the way, all the commentators here, especially foreign ones, wrote: "Thank you China for such a brilliant election result," because the more criticism Takaichi received from China, the more people — especially young people — voted for her. That's all there is to it.

Yuriy Romanenko: And how are they building relations with the U.S. now? They're not going head-to-head, as many would like. But I understand — as you said last autumn and in our last broadcast — they've concluded that the shift in the States is serious and carries risks for their security. And so, without getting drawn into conflicts, they're gradually...

Serhiy Korsunsky: Yes, the Japanese are very pragmatic people and natural-born — I say this completely seriously, the more I observe, the more I'm convinced — simply natural-born diplomats, because they are very composed. You know how Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs commented on Wang Yi's statement that Japan plans to take Taiwan? This is a classic, you understand, it should be studied at the diplomatic academy.

The statement of Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs went like this: "A representative of one country stated in Munich that Japan has interests regarding Taiwan. We would like to explain to the representative of that country that Japan has no interests regarding Taiwan." You understand? They didn't say: "We condemn China, we don't like Wang Yi." This is an official statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. That's the Japanese manner.

The same applies to the United States. First of all, the defense minister traveled there quite recently. If anyone has seen him — I know him very well, personally, closely. This is Koizumi, the son of the legendary Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. He is the defense minister. He went to the United States, had very serious conversations with Hegseth. They even worked out together in the gym — that's also interesting, you understand. And they received assurances that Japan remains a strategic ally and that there would be no reduction in assistance in terms of protection from various threats.

But on the other hand, Japan now has a clear understanding that the matter concerns not so much Japan itself, but that line called the "first island chain." It includes Japan, Taiwan, and Borneo. That is, a group of islands most closely located in the Pacific to China, Korea, Russia, China, and Korea. Well, primarily to China.

The idea is that as long as democratic governments hold power on these islands, as long as American bases are located there, China's access to the Pacific is impossible. That means a mass breakout with the goal of attacking the western coast of the United States. Because the eastern side — that's NATO and the Atlantic, everything is fine there. But the western side... Between, roughly speaking, California and China lies only this island chain. There is, admittedly, a second and third chain, but they are more sporadic.

This is a concept, this is a strategy, not just talk. And it's all grounded in military science. The corresponding forces are positioned at each of these chains. And each will fulfill its function. So this is primarily the interest of the United States — to protect its Western Hemisphere, both Americas, from a possible approach from the Pacific. That's one thing.

Second — Japan has actually already moved toward producing new types of weapons, including various missiles and very interesting underwater and surface systems that will ensure its security. The idea is to push the line of engagement as far out into the ocean as possible. I've heard a figure of a thousand kilometers. Well, perhaps not everywhere will a thousand kilometers be achieved, but the intention is to have the capability to attack an adversary's fleet at long range from Japanese shores.

So they don't openly say... The Japanese — this is a culture of silence. They understand everything, and what they understand regarding the U.S. is roughly this: "If you help us — thank you, we greatly value this and very much want you to help us. But bear in mind that we are also doing a great deal to protect ourselves."

In conclusion, I want to mention a very interesting current topic. They promised 550 billion in investments when Trump visited — he extracted that commitment from them as he did from others. This is very interesting. For a considerable time now the Japanese have been telling the Americans that the question of the mechanism for implementing their investments got stuck in parliamentary committee review. And there it's stuck — and that's that.

Yuriy Romanenko: In this logic, Katya Gudish asks: "Could Japan in the future become the leader of an Asia-Pacific military bloc?" Well, probably one of the blocs, since I understand — well, we see — that China is forming its own bloc there, Japan is also moving in this direction, because with the Philippines just a couple of weeks ago a strategic agreement was concluded...

Serhiy Korsunsky: And before that there was one with Australia, yes. This is... Well, the question is correct. In fact, many countries in the region look at Japan very seriously in this aspect. And this message resonates here constantly — that now the hour has come for Japan to become a regional leader that will unite everyone...

This is not an anti-China bloc, I want to say that immediately. Generally, the Japanese manner, their thinking — it does not create enemies. But it understands the threat. And so yes, this is indeed what is being discussed. And everyone looks with great hope to Japan's role being strengthened. And I am confident that is exactly what will happen.

Knowing Takaichi, knowing her worldview... She absolutely... How to put it... She feels no qualms about stating — and she has done so many times — that we must restore Japan's sense of its role in the region, a role that was lost in connection with the tragic events of World War II. As if that chapter is closed.

Japan has undergone its catharsis. All these years it helped everyone, including... I don't remember whether I mentioned this on air — this figure still leaves me absolutely stunned. Over the course of 40 years, they provided China with technical assistance totaling more than 4.5 trillion yen. Do you know what year they stopped providing this assistance? 2022. In 2022. That is, from 2010 China surpassed Japan in GDP, and Japan continued providing it technical assistance for another 12 years after that. And finally stopped in 2022. You understand? That is, they consider the matter closed.

With Korea, with the Philippines, they are creating mutual security mechanisms aimed at keeping China in reasonably decent behavior with respect to the South China Sea. And regarding Taiwan — China keeps demanding she take her words back, but she has said this will not happen under any circumstances. "If China wants to be friends with us — we're ready. If China does not want to be friends with us, then we will continue to follow our policy as we see our country's national interests." And accusations of militarism and other such nonsense she categorically rejects. And I want to confirm this — there is nothing even close to that in any form in Japanese policy.

Yuriy Romanenko: George Friedman gave us an interview last week dedicated to middle powers.

Serhiy Korsunsky: He has books — "The Next 100 Years"...

Yuriy Romanenko: There was "The Next 10 Years," then "The Next 100 Years," he had many books — "Flashpoints," I think, was another one. And he specifically, after Mark Carney's speech in Davos, went after the so-called middle powers, and he had this key thesis — I can even provide a quote now. He was asked by journalist or analyst Christian Smith: "What do you think about the idea of middle powers as an alternative to China and the United States?"

And he says that middle powers will find it very difficult even within alliances to replace China or the U.S. and serve as a serious geopolitical alternative. According to his data — the United States is a quarter of the world economy, China is 20 percent. So all the rest account for 55, just over half. If you count countries with a GDP above a trillion, there are about eight such countries. They divide half the world economy among themselves. These are relatively small countries. If you expand the list, the economies become even smaller.

In other words, the idea that these countries can unite and stand up simultaneously to the U.S. and China, creating a new economic system, assumes that the middle powers themselves will absorb all this export and ensure each other's economic survival. For example, Canada directs 75% of its exports to the U.S. and approximately 15% to China. If it loses both markets, it will have to find sufficiently large alternatives. And among countries with GDP over a trillion — about eight. Divide half the world market among those eight countries. None of them individually, nor all of them together, are a sufficient market for the rest of the world. First, the numbers simply don't add up. Second, these powers are scattered all over the world. I would call Germany a middle power. South Korea too. Russia by this criterion too. And so the question is: how will Germany ensure the security of South Korea, which is right next to China? A wonderful idea — unrealistic, impossible.

He further says that the values of South Korea and Germany are fundamentally different from Canadian ones. In some sense kindred spirits, but culturally completely different. Though it's not about hard power. The economy is not hard power, but it's absolutely necessary for export-oriented countries. Both Canada and most others are exactly that. They need markets. The bottom line is: the U.S. and China control nearly half the world economy. These countries must find a replacement for the appetites of China and America. A difficult task. Add to this that without security there is no economy. There is nothing more dangerous than being rich and weak — they'll come for you. Don't sit down at a poker table, throwing out a pile of money, if you don't know how to play.

Essentially, the idea is that these countries can balance each other, then balance the great powers — China and the U.S. From an economic standpoint, this is arithmetically absurd. And at the same time, however you reason about soft power, military might is a mandatory condition. If you have an economy, you must protect it. There are predators in the world. So these people, gathered together, would make an interesting group that has regular dinners together. But can they exist outside of the two largest powers, without economic and especially military relations with them? That is hard to believe.

But based on what you've been saying, it seems that — I understand this now — the bet is not on some abstract alliance of everyone with everyone — Europe, Canada, countries of Eastern and Southeast Asia — but rather specifically on Eastern and Southeast Asia, where there are interests, and that's where the bloc will be coalescing.

Serhiy Korsunsky: I agree with Friedman insofar as he means opposition outside of both hegemons, meaning the U.S. and China. But I think that's a very artificial scheme. Yes, of course, especially here in Asia. The ASEAN countries, for example, have been saying for many years that they would not want to choose between the U.S. and China. For everyone here, China is the largest trading partner, and of course no one wants to quarrel with it.

And incidentally, this quarrel between Japan and China — so visible on the international stage — does not prevent the continuation of intensive trade, and several hundred, if not thousands, of Japanese companies continue to operate in China. So in reality these processes are indeed under emotional pressure, but they continue. And again, this does not mean that in countries like Singapore or Indonesia or Malaysia, the United States is ignored. That's out of the question.

There are, first of all, economic models that depend primarily on domestic consumption. In the United States, for example, for a significant number of years — if not the entire post-war period — the economy developed exclusively through domestic consumption. A tremendous circulation of funds within the country drove GDP growth. But it was also connected to the fact that U.S. goods came relatively cheaply from external markets, because they invested abroad in production.

There are other models, like Japan's. This is not a consumer society. Its economy exists because of a positive trade balance. That is, Japan sells more than it buys in monetary terms. And here begins financial policy — the question of the yen exchange rate against the dollar and so on. But simply put, this society develops and its GDP grows or not independently of domestic consumption.

I'll even tell you something... Few people know this — that in Japan, even though its external debt is very large — something like 10 trillion dollars — the fact is that the population has 15 trillion sitting in bank deposits. You understand? Few people know this and few can believe it. And this continues even now when the economic situation in Japan is fairly difficult — that is, prices are rising but wages are not. Yet the population still puts money in banks. They don't take it to the stock market like in America.

Therefore the resilience of this economy is extraordinary. The Japanese are also the largest holders of U.S. external debt. So it's not just about GDP, you understand? It's also connected to trade policy and to the economic model that either drives it or doesn't.

After all, Japan has had 1% GDP growth for 30 years. That would have brought everyone else to their knees. China, if it has less than 6 percent, is simply stagnating. Japan functions just fine at one percent. And when Warren Buffett came here two years ago and bought 10% stakes in each of Japan's five largest conglomerates, the world gasped. That is: "Wait, how? But we've been saying for 30 years that Japan is stagnant and everything there is terrible."

And Buffett said: "You know what? While you're playing roulette and someone will get their GDP growth and someone won't, Japan will give you 1% under any circumstances." That was the answer. I witnessed this, because I was following this process. After that, BlackRock came here. Of course — because if Warren Buffett showed up... You understand, that says something about the fact that there are different models.

And one can't focus — just this simple scheme — on GDP level and relate these middle countries to it. Let's recall a few more middle powers. Such as North Korea, Israel, Singapore, and so on. They exist and ensure their security and their place in the world without relying on some enormous resources and some enormous forces.

Yes, we understand that in one case, with Israel, it's the support of the U.S. — enormous support. In terms of North Korea, it's the support of Russia and China. In Singapore there is an agreement among several countries that this will be such a pocket of stability. But I just want to say that in reality, the scheme in the world is slightly different.

The question today — it no longer stands in the context of trade policy, as I see it, because the chaos with tariffs and the collapse of the World Trade Organization has not yet been fully grasped by everyone. Some processes are still continuing by inertia. But in reality, of course, a serious change in logistics chains and markets and so on — large states will work on this.

But the problem is different. The problem is security — the fact that the security architecture has collapsed. And here the role of middle states, which Friedman talks about, is in my view significantly greater than he assesses it to be. Because even if we take into account who among them is a nuclear state, we'll see quite average, let's be honest, states among them.

That is, the question is not what the GDP size is, but whether there is political will to produce the corresponding products and concentrate state efforts on this. Europe, for many years — all the post-war years — felt very comfortable. It built a fine consumer society with a high standard of living, fairly stable. And of course, now there's no desire to spend money on defense, which the United States used to provide. But there is no way out. There is no way out.

And incidentally, I'm glad to hear it increasingly in various sources and publications... Karl Bildt recently spoke about this. And in Munich many spoke about it — that it's time for Europe to create a military union separate from NATO, which would ensure Europe's security against one specific enemy.

That is, the talk is not of some global presence or dominance, because when the United States is involved, there is global representation. If it will be the European Union, it will be against a specific enemy. I don't think that will raise questions for anyone. Even China agreed to this.

Yuriy Romanenko: Well, based on what you're saying, it turns out... I think you're right that Friedman doesn't see that when he makes his thesis about the necessity of security as the key factor for a strong economy... And accordingly, that middle powers must run under the umbrella of either China or the U.S., which the U.S. is already ready to provide. And in fact, their strategy really is — the U.S. doesn't want to, and China doesn't want to. So like it or not, they're pushing them toward independent navigation, as Japan is demonstrating.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Exactly.

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes. And therefore they will guarantee their own security. And here what Alexander Chikmarev writes in the chat: "That is, roughly speaking, in the foreseeable future, the rules of the game in the world market will be defined by powers that don't consume, but produce. And yes, countries will face problems, as China has already entered tight life-markets and will flood them with its goods." The key question here is also not just what they produce, but what they are capable of producing.

Because when Karol Nawrocki yesterday speaks of Poland needing nuclear weapons and planning to make them, for nuclear weapons you need nuclear reactors, and these are all long cycles. Building reactors, building centrifuges, getting nuclear scientists...

Serhiy Korsunsky: You know what the problem is? Tests need to be conducted somewhere. Where will they detonate? Under Kaliningrad, perhaps?

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, and in this regard Japan has far more capability to obtain nuclear weapons, because it has an enormous number of nuclear power plants and is technologically advanced. And so I think they could, within half a year, a year, they could quietly already have nuclear warheads.

Serhiy Korsunsky: They can do this elementally. These three principles — not to produce, not to possess, not to deploy nuclear weapons — these lay at the foundation of all of postwar Japan's policy, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But if things get really dire, if they are forced to, doing this presents no problem whatsoever.

Yuriy Romanenko: How is China feeling now in the new year? Because yesterday one of my subscribers — well, we just communicate with him regularly — he lives in Shenzhen, and he sent me an interesting video, literally from the field, as they say, where he's walking down the street and says: "Look, here's a huge commercial district, things are always bustling here, there's a huge number of various stalls and so on, particularly commercial outlets for visitors, because the Shenzhen locals — they're wealthy, they've been living off rents for a long time, they have real estate, they rent it out to traders, and those traders earn the money."

So he shows me: "Look," he says, "we have this Chinese New Year right now, and" — he says — "there used to be an absolute sea of commerce here." He shows me — everything is closed, nobody, nobody's working. I didn't see a single open shop. And he says: "This is about the real state of the economy — not everything is as rosy as they paint it for China."

And Shenzhen, for those who don't know, is probably the most developed economic region — Shanghai may be more significant, because Shenzhen is where all those first experiments were launched under Deng Xiaoping, and they really took off in a serious way. I was there once, simply amazed by the dynamism of that city.

Serhiy Korsunsky: You know, there are various opinions on this, no one knows for certain, because China is behind the Great Wall. But from my data, which is confirmed by those who are, in my view, absolutely qualified to judge China — from various sources, both in Taiwan and here in Japan... I can genuinely say that I have not heard a single assertion that things are going well in China. On the contrary, I am constantly told that China has very serious economic problems.

They are connected, beyond all other parameters, to the fact that China's provinces were conducting independent economic policy. Beijing was sort of telling them: "Okay guys, develop yourselves, go ahead, we'll see who crosses the finish line first." So they reached the finish line, having taken out enormous loans from banks, having accumulated debts that are absolutely not paying off. That's the first thing. Second, they have staggering youth unemployment, which they find deeply troubling. They have a declining population, which is felt even at Chinese scales. So the economic situation there is really serious.

And since the previous plenum, there has been a threat of Xi Jinping's removal from power, because... I couldn't believe it, but I saw confirmation of this in the press — do you know how they're fighting economic problems? They made a decision to increase the number of hours devoted to studying the history of the Communist Party of China in schools and universities. This was presented as the key measure for increasing labor productivity. Well, how do you say... I remember late Brezhnev, but even there it wasn't quite this level of absurdity.

And with Xi Jinping, people constantly say: "Instead of Deng Xiaoping's economic measures, the open-door policy that brought China to prosperity, you're tightening communist screws." But he can't do otherwise, unfortunately. And then there were purges, and we see these purges. Why in the military? Because that's the only force that could simply topple him.

But the situation there is very complicated. So no one understands why they're now stirring up... And with Japan, which has always been for them a source of technology and investment, why they started a quarrel. There is this opinion that this is the tactic — the well-known tactic of autocratic regimes — of exporting internal problems outward. That is, if you have serious internal problems, you start some little war in order to boost the national mood with patriotic slogans.

And this is precisely what's behind the tension around Taiwan that arose at the end of last year, when they were conducting some extraordinary exercises, and this year it's most likely related to this as well. But as far as I know, the United States warned China fairly clearly that this situation is unfavorable and shouldn't be developed further. We're ready to talk with you and agree on some principles of interaction. And Trump has said several times that Xi Jinping is his great friend and a great leader. But regarding Taiwan there was a warning that perhaps we should be more careful. After which a large arms shipment was sold to Taiwan.

So the situation remains tense, but today I see no immediate danger of intervention. As for China's economy, it is not in such brilliant shape. I think they would now be... That's why in some of my interviews I've spoken about this. It seems to me that today there is a moment when a united Europe — but united in the sense not of the EU, but of those countries that are genuinely concerned about their security and can ensure it...

This would be a Scandinavian belt, Central European, plus Britain, plus Germany, possibly plus France. If they were speaking to China with one voice, I think progress could be made — both in putting Putin in his place, and in creating some new system of trade relations and security in Eurasia. It seems to me that there is a window of opportunity right now. But it will close very quickly. It will close when Trump goes to China. Because we can't imagine what they'll agree on.

And most likely, Trump will still want to bask in the glory of being the one who stopped the 28th war out of 30 that generally exist. He's already stopped the rest. And that's a certain danger, because he is uncontrollable, unpredictable. Of course he's very influential. Of course he could do much good, but we're watching every step. This is all to say that the situation in China today is very ambiguous. You cannot say this is an absolutely stable economy or an attractive social model. No.

Today in the Asian region China is greatly feared, because its aggressive steps are visible. And today its economy is far from being in the position to dictate an economic model to the rest of the world. So there is much to think about and discuss and work on here.

Yuriy Romanenko: Let's jump back to the States. There's another storyline I thought about — the American maneuvers in the Caucasus right now — I think you're following them too, because that also fell within your area of competence when you were ambassador to Turkey. And this visit by Vance, first to Armenia, then to Azerbaijan, after which they announced normalization of relations and the beginning of a large geopolitical game in the region.

To what extent, in your understanding, can this line be a manifestation of some new successful foreign policy of the Trump administration? Because essentially they entered a situation that had genuinely been very problematic for a long time. It's not even that they managed to get Aliyev and Pashinyan to the table — Aliyev himself, I think, was moving for a long time toward his triumph and was very carefully building his system of alliances. In my view, this is generally, if not a brilliant, then a very good example of competent foreign policy implementation by a small state in extremely difficult conditions.

And now the Americans have essentially picked up this situation and are integrating it into the framework of their game regarding Iran and the Middle East. But in principle everything looks like a workable scheme, because the little train, as they say, is running. Oil products are flowing from Azerbaijan to Armenia, and trade will apparently follow. And they're building special relations with both countries, because the Armenian lobby is strong in the States and there are interests to lobby for. And Aliyev is working masterfully — Trump praised him, practically put him in a separate league.

So I think it's quite a workable model that Ukraine could look at in terms of what mechanisms can engage the major capabilities that the States still have, despite all the Trump chaos.

Serhiy Korsunsky: I think you've noticed this American activity. After all, the Caucasus — like the Balkans — you might say these are two regions where something is always happening. Conflicts are always brewing, occurring, and so on. And the Caucasus... Russia has always fussed over this well-known Soviet definition — something like the "underbelly of Russia" — this is the place from which threats to Russia can originate.

Under this idiotic concept, and against it, was the intervention against Georgia in 2008 — constantly claiming that in the Caucasus you cannot allow some incorrect development of events. I even recalled at some point that in 1922, when the Soviet Union was being created, its founders, besides the RSFSR, Ukraine, and Belarus, included the so-called Transcaucasian Republic. That is, it was precisely the fourth participant in the first version of the USSR.

And when I spoke with specialists about this, I was told that yes, this is indeed the concept for Putin — that by seizing Belarus, Ukraine, and effectively controlling the Caucasus — Georgia through occupied territories, Armenia and Azerbaijan through Nagorno-Karabakh — Russia dreams of a new Soviet Union. Symbolically in 2022, after capturing Kyiv, conduct such an event — to restore it on the centennial of the USSR. Believe it or not — this conspiracy theory was told completely seriously.

And I think there are grounds for it, because among other things, Turkey's interests in the Caucasus are enormous, traditionally. And as if Russia had not become mired in the absolute darkness of its current fascism and this diabolism connected to the war against Ukraine, I think they would not have allowed such a development of events. They would undoubtedly have intervened. They simply can't anymore. Just as they can do nothing about Transnistria, they can do nothing about the Caucasus.

And the Americans sensed this very opportunely. Well done. And you're right — this too must be acknowledged, that from both Armenia and Azerbaijan non-trivial steps were taken to acknowledge the situation and resolve it. For each of these countries, Nagorno-Karabakh was declared a sacred place. And none of this was simple at all. Each of them made some concessions, some compromises.

And now I think that Rubio is actually showing an example. Look: even enemies who were in confrontation for so many years, who occasionally resumed hostilities, people died... As a result, the situation has been restored, resolved, and moreover, a positive dialogue is taking place between them.

I've even seen reports that Turkey may now resume relations with Armenia too, as it was until roughly 2009. When I first arrived as ambassador to Turkey, President Gül of Turkey was going to football matches in Armenia. And then they had another serious falling-out. And since then again no relations. But on the border between Armenia and Turkey stood a Russian military unit. There was a Russian flag there. Now it's not there. You understand? And now Turkey said: "Oh, excellent! So now, when no one is getting in our way, let's resume relations with Armenia, then finally put aside the 1915 genocide, and we're not opposed."

I even think this can be expected, but here the game is more complex, because Erdoğan is a very serious politician in terms of constructing various clever schemes. But I don't rule out that this is possible.

First and foremost, it is undoubtedly a blow to Russian interests. This is a great benefit for the region. Another benefit — we have never talked about this in any of our broadcasts anywhere — the Kurdistan Workers' Party has laid down its weapons. I want to tell you that after 40 years of terrorist attacks, the Kurdistan Workers' Party just laid down its arms and declared it is no longer at war with Turkey. That carries tremendous weight. So I don't rule out that there are American efforts behind that as well. And all of this — this is a big positive. I'll say it plainly — both for us and for the international community.

And so this is yet another place where Putin has lost. A genius strategist he is — in quotes, in very large quotes. That is, he awakened Germany, he awakened Japan, he alarmed all of NATO, he so to speak created miracles that we previously could never have imagined even five years ago, you understand? Well, he made his move and received an answer in the form of — as we've already mentioned — middle states, which it turned out can build their policies very interestingly and in general without particularly looking over their shoulders at either China or Russia, and simply at some point understanding that compromise must be sought, even if it is painful.

Yuriy Romanenko: Now let's return to Japan and, regarding Japan and Ukraine — because in principle everything looks favorable for Ukraine in the context of Sanae Takaichi's victory in these recent early elections. Because Zelensky congratulated her on the victory, and she wrote a fine message: "Ukraine and Japan will continue to work together for peace and prosperity," emphasizing the importance of partnership in security, innovation, and mutual support.

And behind such diplomatic formulations — which the Japanese do brilliantly — lies the fact that they give us generators, and provide assistance, and in reality...

Serhiy Korsunsky: They give money — another tranche of 544 million dollars.

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, yes, yes. That is, Japan — in conditions of this greater subjectivity in the security sphere — is demonstrating in principle a sustained interest in Ukraine and its support, because I understand they view Ukraine as a kind of balancing factor in their game with Russia.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Well, honestly, I don't think they look at it as a balancing factor. The Japanese do have their holistic vision of the world and the principles on which this world should be built. Russia's war against Ukraine was a violation of all these principles. And this was rather the basis for Fumio Kishida — as you know — to unambiguously take our side.

Takaichi understands very well what is happening, first of all. She sees the threat clearly. And the Russians constantly provoke the Japanese — whether by flying aircraft in or sailing ships, including intelligence vessels. They... I've forgotten the figure, but it's something like hundreds of sorties they were forced to conduct last year to intercept various Russian flying and floating objects. So they are very clearly accountable about what Russia is.

But at the same time, I also want to tell you this — there are interesting facts that need to be understood when we talk about Japan. Simultaneously with her — and the Japanese Foreign Minister — confirming unequivocal support for Ukraine — and I have not the slightest doubt that this will all continue — simultaneously with this, additional visa centers have been opened in Moscow and St. Petersburg to handle the absolutely extraordinary, doubled number of Russian tourists who want to come to Japan. There are no direct flights, they all fly through third countries.

At the same time, Japanese citizens are permitted to visit Russia — previously this was not recommended — including for academic and research exchanges. A Russian culture festival is being held in Japan. It doesn't receive support from the Japanese government, but the Russian Ministry of Culture and the Russian embassy are not prohibited from conducting cultural events here.

Meanwhile, the former Russian Ambassador to Tokyo, Galuzin — who is today Deputy Foreign Minister under Lavrov — this is the scoundrel I was at war with while he was ambassador, and they summoned me to Moscow — he stated, and Zakharova said the same, that relations between Russia and Japan have passed the point of no return, that they are so bad that they will never return to anything.

Russia... Takaichi herself is under Russian sanctions, as is the cabinet, as are almost all members of parliament. So none of that has gone away. Sanctions are being upheld, funds from interest on frozen assets are being disbursed as part of the G7 program. But at the same time Japan considers it appropriate to continue people-to-people exchanges, apparently believing that taking a categorically hostile position toward any Russian is something they refuse to do. And this too corresponds to their mentality.

Of course, this can't be pleasing. Of course, this has been going on for more than a year. But now under Takaichi, the policy has become very multifaceted. And I think there's nothing we can do about this. We just need to understand that the Japanese have this mentality. What they consider good, they consider beneficial and conducive to harmony in the world. Let them come, let them see.

I'll tell you, in Tokyo this is very noticeable. In the city center, I haven't seen anything like this in many years. Not during COVID, not even in the first years of the war was it like this. There are so many Russians around that it's simply unpleasant to walk through Ginza. But they are there. That's a fact. And they keep a very low profile, incidentally.

So the Japanese — they're interesting in this regard. That is, there's a principle — and they follow it. But there's another principle — and they follow that one too. You know, even during World War II, while fighting the Chinese, they erected monuments to fallen Chinese soldiers and paid their respects. And when Roosevelt died, the Japanese government expressed condolences to the American people. Can you imagine? That is how Japan is structured — it is a separate civilization, even by Huntington's definition.

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, interesting. So taking into account the atrocities the Japanese committed in China, and yet building these monuments along the way — that's very interesting indeed.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Because a samurai must respect even his enemy. Before cutting off his head, he will certainly bow to him.

Yuriy Romanenko: Here viewers are asking — Lola asks: "Could the next broadcast be about Turkey? Its interests in Ukraine and vice versa, Ukraine's mistakes, who will support or the factor of Crimean Tatars?" In short, a large systematic broadcast of this kind.

Serhiy Korsunsky: I left Turkey 10 years ago, though of course 8 years weren't wasted.

Yuriy Romanenko: Well, yes. Well, I can't speak about modern things I'm no longer tracking, but in principle Turkey, of course, will forever be in the heart, because I arrived when Turkey was entering the EEC, and left when there was a military coup. Between those two events, a great deal happened.

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, well I think let's do it, because I love Turkey myself, I'm interested in it, and it's... Because when you mentioned the Kurds, that there's an American trace — of course there's an American trace, and it was cleverly tied to Erdoğan's agreements with the Trump administration, and they extinguished the Kurds there, very skillfully. And credit must be given — it was done very systematically, they worked for decades. This is what I think is generally an example of what long-term will and patience in a state's foreign policy looks like — just like with Aliyev and Karabakh.

So here with the Kurds Turkey is simply demonstrating how to approach the systematic resolution of one's problems and achieve success.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Agreed.

Yuriy Romanenko: Good. Thank you very much for giving us your time.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Always.

Yuriy Romanenko: Perhaps in a couple of weeks we'll do a broadcast on Turkey...

Serhiy Korsunsky: I'll say this — the country... You know, I really in this regard was very fortunate, because Turkey — it is also very layered, very complex. I always said this while working there, and I say it to students afterwards: if you've simply been in Turkey in Antalya, you haven't seen Turkey. And even if you've been to Istanbul, you haven't seen Turkey. Turkey is Central Anatolia — you need to go deep there into the mountains, see the people there, go to Diyarbakır, go to Gaziantep, to Konya, to Şanlıurfa, look at the dervishes in Konya.

You need to immerse yourself very deeply in all of this, and then you'll begin to understand that this country is very complex. Erdoğan is genuinely deserving of credit — he is a genius at how you can govern such a complex country and keep it afloat, and moreover strengthen its authority in the world. But there are a million fascinating nuances to discuss, including in relations with the United States and with Russia. It too pursues such a policy — playing both sides, maneuvering between them — like a proper middle state that understands it has something with which to respond to any threat, but there's no need to unnecessarily provoke madmen, of whom there are still plenty.

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, 100%. Good, then in two weeks we'll do such a broadcast. Many thanks to Serhiy Korsunsky. Such a voice of reason from Japan. Until the next meeting.

And by the way, I want to tell you that your broadcast performs very well — one of the clips from our last conversation got something like 300,000 views if I remember correctly. So...

Serhiy Korsunsky: Wonderful!

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, so they say people fall for all kinds of nonsense, but they also watch such serious content with great pleasure.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Good, thank you very much.

Yuriy Romanenko: Yes, have a good evening.

Serhiy Korsunsky: Thank you.